A new report says the region remains an economic powerhouse — but Donald Trump’s America-first agenda has some analysts concerned

The Great Lakes region, comprising two provinces and eight states, boasts a larger economy than Japan, Germany, and the U.K. (TVO)

Economies in the Great Lakes region grew faster than the Canadian economy last year, pulled along by Ontario, Quebec, and Indiana, according to a report released Tuesday morning by BMO Capital Markets at a conference in Detroit.

This year, Ontario is expected to lead the country with GDP growth of 2.6 per cent, “topping the national average on a sustained basis for the first time in more than a decade,” the report says. Auto production, a weak Canadian dollar, housing in the GTA, and low oil prices are all contributing to strong growth in the province.

“While some headwinds have kept the pace of growth in check south of the border,” the report notes, “most signs point to a stronger expansion in 2017.” The two Canadian provinces and eight U.S. states that surround the Great Lakes had an estimated combined GDP of $6 trillion (all figures U.S.) in 2016, up from $5.8 trillion the year before. If the region were a country, it’d boast the third largest economy in the world, after the U.S. and China.

“Not only do people not understand how big the economy is, people just generally don’t understand how hugely reliant we are on each other for that success,” says Mark Fisher, chief executive of the Council of the Great Lakes Region, an organization that brings together public, private, and non-profit groups in the area to discuss issues of mutual concern — and that convened the Detroit conference.

“Quite simply, the economic importance of the region can’t be overstated,” the BMO report says.

Traditionally the industrial heartland of North America, the Great Lakes region still has a bigger-than-average manufacturing sector. But today, manufacturing accounts for just about 11 per cent of employment in the region, down from 15 per cent a decade ago. Job growth is now driven by services, particularly health care and education.

Indiana and Michigan had the highest employment growth in 2016, at 2 per cent each, but Ontario still came in above average for the region, at 1.1 per cent.

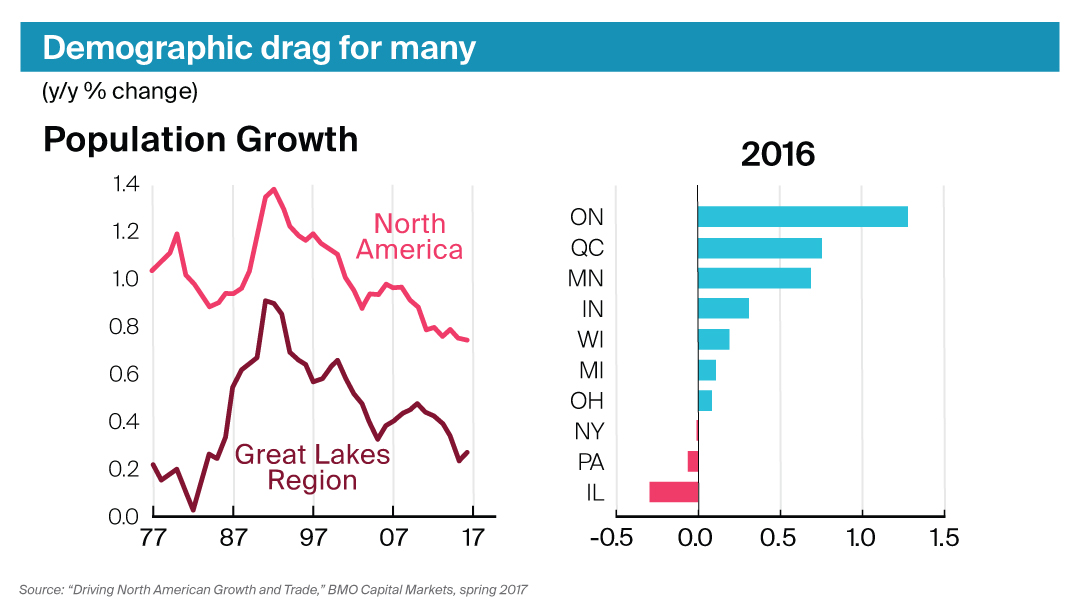

Slow population growth — due to aging demographics, relative economic performance, and normal business cycles — will continue to be a challenge in the region, BMO reports. The Great Lakes provinces’ and states’ populations are growing at an average rate of 0.3 per cent year-over-year, less than half the North American average.

But Ontario and Quebec are doing better than the U.S. states, the report says, because they welcome immigrants with open arms. Recent migration into Ontario from provinces such as Alberta (where low oil prices have forced workers to look for jobs elsewhere) helps, too.

Another challenge for the region will be the state of Canada-U.S. trade relations, especially given the uncertainty introduced by the Trump administration. President Trump has decided examining trade surpluses and deficits is the way to measure the fairness of trade deals. Lucky for us, the report finds, U.S. deficits with Canada are negligible, at just $16.5 billion (compared to $350 billion with China and $69 billion with Mexico).

The Great Lakes region drives North American trade. BMO’s report notes that 60 per cent of Canadian shipments to the U.S. come from Ontario and Quebec alone.

But our interconnectedness also explains why Canadian officials are worried about Trump’s “Buy American, Hire American” executive order.

“Great strides were made in the last couple of years at the federal level and the state/provincial level to get to a more common understanding of how we invest and support each other’s economies,” Fisher says. “I hope we’re not shifting away from that.”

Trump has a penchant for making panicked and overblown comments about trade. But compared to America’s issues with other countries (e.g., China), its issues with Canada are the equivalent of a mosquito buzzing around your head on a hot day — irritating, but ultimately insignificant.

“When people raise concerns about cheap Chinese steel coming into the U.S. marketplace, that is fundamentally different than the things that we make together and sell together,” Fisher says. “U.S. iron ore turns into Canadian steel which is then resold into the U.S. marketplace. So steel from Canada is as much U.S. steel as it is Canadian steel.”

Fisher says policy makers need to understand that protectionist procurement measures do more harm than good.

The Great Lakes conference takes place Tuesday and Wednesday, mostly in Detroit (with one event happening across the border in Windsor). Fisher hopes discussions there will promote greater awareness of how important the Great Lakes states and provinces are to one another. Ontario seems to get it, he says — the Americans less so.

“I continue to be struck by the lack of awareness by business and policy makers about how interconnected we truly are and the things that we could be doing together to create more growth, through shared initiatives around infrastructure, regulations, energy, talent, mobility of professionals,” Fisher says. “If we were to have a much more integrated conversation, we could easily make this region a lot stronger than it is even today.”