Inside the Cargill Family

/

Family business profile, written for the Creaghan McConnell Group:

It’s the largest commodities trader in the world, employs 155,000 people, and operates around the globe in a wide range of industries. Sales and other revenues totaled US$114 billion in fiscal year 2018, making it the largest privately held U.S. company by revenue, according to Forbes.

Chances are, you’ve had a taste of one of its products at some point in your day. An egg from McDonald’s. Or a Coke, or a beer. Or anything salted, sweetened, preserved, emulsified, or with added texture.

Candy bars, pretzels, canned soup, yogurts, ice cream – all include food additives that probably come from the company’s line of food ingredients – a business that, on its own, was worth $50 billion in 2015.

And there’s a decent chance you’ve never heard of it.

The company – and the family business – is Cargill.

THE REMARKABLE STORY OF CARGILL

Through its long history, Cargill has remained notoriously quiet. We rarely hear about the 100-plus Cargill and MacMillan family members that control the company. We’d be hard-pressed to locate Wayzata, Minnesota (where Cargill is headquartered) on a map.

The company has a sustained record of innovation and growth that has spanned more than a century and a half – all while staying private. It’s a remarkable accomplishment for a business today – especially for one of Cargill’s size – when the pressure to go public can be overwhelming.

It hasn’t been always easy. Cargill, like entities owned by most business families, has endured its share of internal struggles about how the business should be run. Cargill has the added challenge of having more than 100 different family members that own shares in the company. Wrangling consensus with that many stakeholders can be challenging at the best of times. When family relationships and money are on the line, the obstacles become even more significant.

Over the years, there has been occasional discord between the two owner families, the Cargills and the MacMillans. As the family (and business) have grown, so have the pressures from some younger family members to go public and “cash out.” Through it all, Cargill has found creative ways to manage, grow – and to endure. The family has bridged its divides with imaginative solutions, including creating a family office that helps manage the needs of the family and fosters engagement and learning among the younger generations.

The story of how the Cargills and the MacMillans have managed their issues and committed to a long-term vision to keep Cargill innovative – starting from a single grain warehouse in Iowa – is impressive. It’s an inspirational example of how successful business families persist and succeed.

So, let’s look at a bit of its history.

A history of agricultural innovation

William Wallace Cargill founded Cargill Inc. in 1865, at the end of the U.S. civil war. He owned a single grain storage warehouse at the end of a lonely rail line in Conover, Iowa.

Grain warehousing was a novel concept at the time. Most farmers lacked the resources to store their own product, and were at the whim of transports and market prices. If they couldn’t move their grain in a timely manner, it would sit and rot, or sell at discounted prices when they were finally able to move it. Cargill offered fair rates to farmers for their grain, and then stored it until the time was right to sell at a profit.

As the railway moved west, so did Cargill, building more warehouses, terminals, and grain elevators. Three major terminals were built in Minnesota alone.

The MacMillan family joined the ranks in 1895 when W.W.’s daughter, Edna, married John MacMillan, who took over the company when W.W. died. Later, when MacMillan inherited the company in 1912, the company was over-leveraged. It was also facing a failed investment in a Montana irrigation project that had left Cargill’s financials in dire straits. To keep the company afloat and bankers confident, MacMillan restructured the company. He renegotiated loans, extended debt payments, and sold off less profitable parts of the company.

One particular move by MacMillan had a lasting impact – a change to Cargill’s leadership structure. The MacMillan in-laws were given controlling shares in the company, while the Cargill family members became minority shareholders.

Within six years, Cargill had paid off all of its debt and was growing again.

Through the early 20th century, Cargill made big bets in new markets and technologies. The company acquired a grain merchandising firm with a private wire communication system in 1923, a strong competitive edge at the time. After World War II, Cargill diversified, acquiring a feed business and a soybean meal and oilseed processing plant.

Cargill’s fast growth continued. From 1950 to 1980, it expanded aggressively around the globe, establishing separate companies in Europe and Asia, all while developing a centralized research and development arm of the company. In the 1960s, for the first time, the family decided to hire an outsider to run Cargill. Erwin Kelm is credited with modernizing the company, and moving it into these new markets.

The last member of the family to run the business was Whitney MacMillan, who oversaw

a significant expansion of Cargill’s product lines, into industries including chemicals, cocoa, coffee, financial services, peanuts, petroleum, poultry, rubber, steel, and wool. He retired in 1995.

Relentless change

Today Cargill operates in 70 countries. The company has topped the Forbes list for privately- held companies an astonishing 28 out of the last 30 years. Beyond grain and oilseed processing and commodities trading, Cargill is invested in steel, financial markets, risk management, ocean transport, salt, bio industrial, food and specialty ingredients, animal feed, pharmaceuticals, beauty and personal care, and meat and poultry.

A key to its success has been a continuous discipline (and willingness) to innovate.

Playing the middleman between farmers and their customers was a lucrative business model for many years, but today farmers can find the price of grain or weather patterns anywhere in the world with a few clicks on their smartphones. Digital disruption has come to agriculture just as it has in most other industries.

Leading the charge, Cargill continues to invest in innovative new technologies and look to future global demand. The 154-year-old company now sells facial recognition software to enable farmers to identify individual cows and monitor their food intake and milk production. Another app helps assess the quality of animal feed. And the company has a new system, iQuatic, that works underwater at shrimp farms, monitoring water movement

to determine when food should be automatically dispensed.

In 2018 the four largest agribusinesses in the world – Archer-Daniels-M+idland Co., Bunge Ltd., Cargill Inc. and Louis Dreyfus Co., known as the ABCDs of the industry – joined together to standardize and digitize trade. These companies are now looking for ways to cut costs and increase transparency using blockchain and artificial intelligence.

Cargill is also betting big on a growing global demand for protein. The company is already

the world’s largest supplier of ground beef, and second-largest beef packer. But now Cargill is also investing heavily in aquaculture, most notably acquiring Norwegian company Ewos, one of

the largest salmon feed producers in the world, for $1.5 billion in 2015. It has also invested in Memphis Meats Inc., a “clean food” company, that grows chicken, duck, and beef directly from animal cells, without raising and slaughtering livestock, and Puris, a company that produces non-GMO and organic proteins from peas and other vegetables.

Of late, animal feed and proteins have been Cargill’s largest source of revenue, accounting for two-thirds of net income, the largest contributor to earnings in the last two fiscal years. Analysts believe the company will see less and less of its revenue come from commodities trading in the years to come.

A massive firm, still privately owned

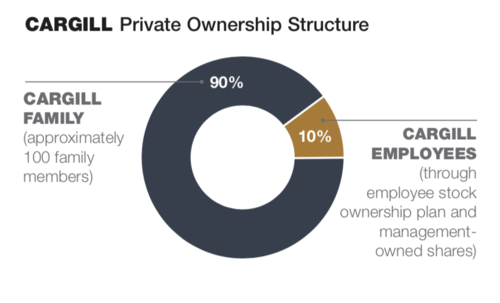

Today, roughly 100 members of the Cargill and MacMillan families control about 90 per cent of the shares in the company. The remainder is made up by an employee stock ownership plan and shares owned by management.

The company pays its family members 20 per cent of annual returns in dividends, with the balance consistently reinvested in the company. Compared to other companies, family members receive very little – payouts often reach as high as 50 per cent at other companies in the S&P 500. But the Cargill and MacMillan families have committed to focus on the company’s sustainable long-term growth over their own immediate benefit.

Harmony between the Cargills and MacMillans has, at times, been a challenge, despite the company’s success. Like many family-controlled enterprises, there have been occasional disputes and tension over influence in the company. Some Cargills believe that their family business was “stolen” from them, while some MacMillans have felt that their work in “saving” the business has gone unnoticed and unappreciated.

But these conflicts have also highlighted the need for the families to come together with

a shared vision for the growth and success of Cargill Inc. So they formed Waycrosse, a family office that serves the interests of the families. Originally designed to only provide financial and professional advice, today Waycrosse also organizes training and education programs for the three living generations. It also actively works to ensure family members not working in the company are engaged with the business – through education programs, meetings, plant tours, and task forces.

It’s a big job. Cargill Inc. now has seventh- generation owners. Fourteen Cargill family members are said to be billionaires – “one of the largest concentrations of wealth in any family- controlled business anywhere in the world,” according to Bloomberg.

Even so, with each successive generation, the pieces of the Cargill ownership pie get smaller and smaller. A parent who once owned one- ninth of the company may now be splitting it among, two, three, or four children. Many privately-held firms have gone public by this stage, with younger family members having less personal attachment to the family business, favouring instead to take their large payouts and leave. But Cargill’s current CEO, David MacLennan, says the family has no intention of taking the company public any time soon.

It hasn’t always been that way.

Ongoing liquidity challenges for the family

Even though total shareholder equity was valued at US$33 billion in 2018, some shareholders have struggled even to obtain a mortgage because their assets are not liquid. They’re tied up in shares in the business. On two occasions the company has had to contend with family members who wanted Cargill to go public so that they could cash in.

The situation was diffused once (in 1992) when Cargill created an employee stock plan, allowing family shareholders to sell 17 per cent of their stock for $700 million. And then again, in 2006, the family faced a similar problem, this time because of the death of a family member, who also happened to be the largest shareholder. Margaret A. Cargill, who owned 17 per cent of the company, died with no heirs. Her shares went into a trust, with the primary beneficiary being the Margaret A. Cargill (MAC) Foundation.

Before Margaret’s death, Cargill had already identified the need to meet the family and company’s liquidity and investment needs, while also remaining private. In 2004 Cargill created Mosaic, a fertilizer company, which was the merger of an existing Cargill fertilizer operation with a publicly listed firm. It was the first time any part of Cargill was publicly listed.

Eventually, the MAC Foundation chose to diversify its holdings, and rid itself of the large share in Cargill. So Cargill made a deal to trade off its position in Mosaic. Approximately $12 billion in Mosaic shares were transferred to the foundation and other family shareholders, in exchange for Margaret’s 17 per cent stake in Cargill. Another $7 billion from the Mosaic sale was used to pay down some of Cargill’s debt.

And so Cargill endures, year after year, at the top of the Forbes list for privately controlled businesses.

That the Cargill and MacMillan families have consistently worked through their differences in the interests of growing the company for so long – and so consistently – is a testament to their focus on the long term.

The pressures to go public will inevitably resurface, and the company will have to remain vigilant and nimble to address this ongoing challenge. As the family continues to grow, there will be more and more shareholders holding less and less of the company. And family liquidity will be an ongoing concern.

But if the last 154 years have been any indication, Cargill Inc. looks well equipped to handle whatever comes its way.

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER FOR YOUR BUSINESS:

1. How will you keep your family business private, in the face of pressures to go public

from shareholders?

2. Do your family members believe in the company’s growth strategy, and will

they support it?

3. How is your family addressing its own liquidity challenges?

Sarah Reid is a freelance writer based in Toronto.